My eBook build process and some PDF, EPUB and MOBI tips

|

| Ruby Under a Microscope is an illustrated guide to Ruby internals. No C programming required! |

In case you missed it, last month I self-published an eBook about Ruby internals called Ruby Under a Microscope. To date I’ve sold over 600 copies - thanks everyone! I’ve never written anything so ambitious before, and I’m grateful for your support. I hope it’s been a fun read, and that you come away with a better appreciation for the amazing work Matz and the rest of the core team have done to create such a beautiful language. It was certainly a lot of fun to write!

In the spirit of “sharing is caring,” and to follow in the footsteps of some Ruby self-publishers like Jesse Storimer (see 4 Months of ebook Sales and Lessons Learned Getting Other People to Sell My Ebook) and Avdi Grimm (see My authoring tools) who have been generous with their knowledge, I’d like to try to pass along whatever information I can about how to publish an eBook. This post contains a high level description of my build process for Ruby Under a Microscope, and also a few tips for dealing with the PDF, EPUB and MOBI file formats that I learned along the way. If anyone would like actual code or more technical detail about my build process, or if there’s any other way I can help you self-publish something, please let me know!

My authoring tools

To write Ruby Under a Microscope I used Apple Pages on a Mac laptop. While I love VIM for writing code, I find it easier and more natural to use a traditional word processor to write English text. Also, Apple’s spelling autocorrect feature works nicely; I prefer to use the “Automatically use spell checker suggestions” option in Preferences -> Auto-Correction.

As you might know, Ruby Under a Microscope contains a large number of diagrams - a picture is worth 1000 words, and often I find visual aids are the only way to communicate the complex ideas, algorithms and data structures Ruby uses internally. To draw these I used the Omnigraffle product from The Omni Group. This is an amazing tool that allows you to produce professional looking diagrams very quickly. It also integrates very nicely with Apple Pages; I can copy/paste a diagram from Omnigraffle right into Pages and immediately see something that will closely resemble my final document. As I’ll explain below, I also ended up purchasing a license for Omnigraffle Pro, in order to be able to export my diagrams as SVG vector image files, a feature the standard version does not contain.

The Bookshop gem

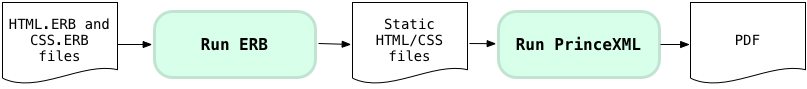

Once I had the bulk of my writing done, I copied my text into a series of HTML/ERB files and used a gem called Bookshop to manage the process of creating the PDF, EPUB and MOBI target files from them. Bookshop, in turn, uses a tool called PrinceXML to create the PDF file:

As you can see, Bookshop is essentially a Ruby static site generator like Jekyll or Middleman: you use it to run a series of ERB transformations that produce static HTML and CSS. Then Bookshop launches PrinceXML to convert the HTML to PDF. PrinceXML is not cheap ($495 US), but has been worth every penny to me. It does a remarkable job rendering the PDF, allowing you to use really any CSS styling/design code you you would like to. With PrinceXML, creating a beautiful PDF file is as simple as - or as hard as - creating a beautiful web site.

PrinceXML also supports a number of print-only related CSS directives you may not be familiar from web development, such as the “page-break-before” attribute or the @page directive. For example, I used this CSS code to indicate I wanted page numbers in the lower left corner for left side pages:

@page :left {

@bottom-left {

font: 8pt "Helvetica Neue", serif;

content: counter(page);

padding-top: 2em;

vertical-align: top;

color: #880000;

}

}

One of the nicest features of Bookshop was that out of the box it provided a series of CSS templates to get me started, containing a series of example CSS styles I could use for page numbers, the table of contents and more.

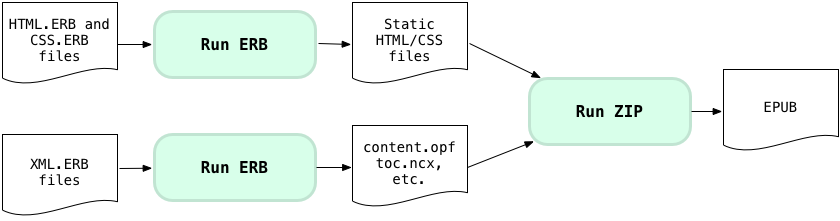

Next, here’s how Bookshop creates the EPUB file:

You can see here that the EPUB is essentially a ZIP file containing the static HTML/CSS source code, along with a few mysterious XML files (content.opf, toc.ncx, etc.) that contain the book’s table of contents, a list of your HTML and other source codes files with their mime types, and other meta data. Bookshop also automatically runs the EpubCheck utility on the finished EPUB file to help you be sure you got everything correct in those XML files.

If you’re really interested in learning the details of the EPUB format, this fun, practical video by Paul Salvette might be worth watching: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RSc7XZzMkq0

Finally, Bookshop launches Amazon’s KindleGen utility to generate the MOBI file from the EPUB file:

Customizing Bookshop

To make my life easier, I ended up customizing Bookshop to support code syntax highlighting (using Coderay) and to allow Markdown as the source file format (using Redcarpet). I also customized it to be able to manage the large number of diagram images files I created in special ways. If anyone is interested in these details, let me know. In a nutshell, I used SVG to represent the diagrams for the PDF, but PNG for the diagrams in the EPUB/MOBI files; using two different file formats for the same images required some code changes to Bookshop.

I’ve also heard good things about the Kitabu gem, which seems to function in largely the same way as Bookshop. I haven’t tried it, but if I write another eBook I’ll probably look at using Kitabu instead, since it already contains support for code syntax highlighting and Markdown. It’s also encouraging that Jesse Storimer, a prolific eBook author, is a maintainer on that project.

PDF tip: use vector image file formats

PDF is the the Mercedes of eBook file formats. I’m guessing most people who read technical eBooks use a PDF file on a laptop: it just works, it looks the same on every platform, and we all have the confidence that the rendered document will appear the same as the original document did. After spending months crafting a PDF file, I’m amazed at what Adobe’s software can do - why read a book using any other file format?

One important but easily overlooked property of the PDF file format is that it is vector based. That means that, like SVG and related image file formats, all of the text and other rendering information in a PDF document is saved as a series of vector commands: “go here, draw this, move there, draw that, etc.” But since the Adobe’s PDF file format is more or less a black box, this doesn’t normally matter: who cares how the PDF file format works internally?

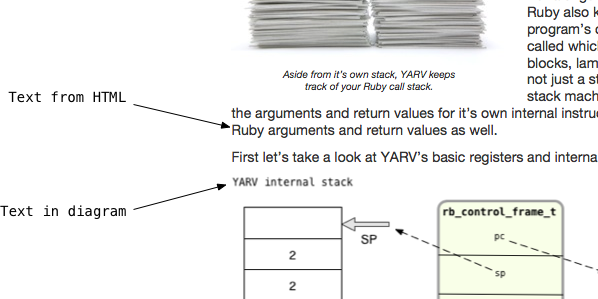

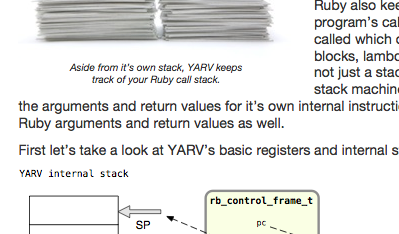

I certainly didn’t, until I tried to render some of the many diagrams in Ruby Under a Microscope in a PDF file. For my first attempt, I rendered my diagrams as PNG images and then included them in my HTML using <img> tags, as I normally do for blog posts. PrinceXML then produced a PDF file that looked like this:

While this isn’t horrible, you can see the “YARV internal stack,” “rb_control_frame_t” and other text in my diagram at the bottom is blurry and somewhat disappointing to look at. The text above, which originally came from the HTML source code of my book, looks fine. It almost looks as if you were viewing the diagram through a thick piece of glass, while viewing the rest of the document directly with the naked eye.

The problem here is that the end user PDF viewer software, for me Apple’s Preview app, has to resize the original PNG image for the diagram, scaling the text as necessary along the way. This produces the blurriness. It’s also possible the scaling is performed by PrinceXML when the PDF file is generated.

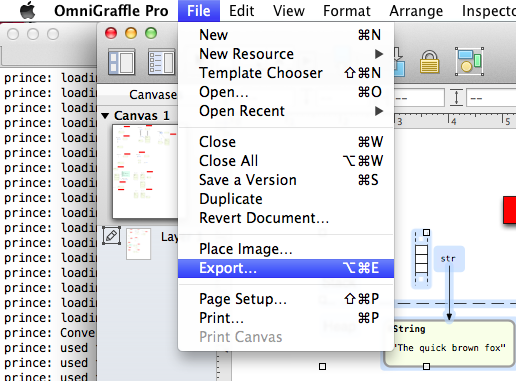

It took me a few days of research, trial and error to stumble upon the solution: since PDF is internally a vector based format, why not render my diagrams using a vector based image file format? After paying some extra money to upgrade to Omnigraffle Pro, I was able to use the “File -> Export” command:

… and then select the “SVG vector drawing” file type (the standard version of Omnigraffle doesn’t support this):

Now the real magic happens: when I include an SVG image in my HTML using a standard <img> tag, PrinceXML generates a PDF file that includes the vector commands to render the diagram! In fact, I also noticed that PrinceXML includes whatever font I used in the Omnigraffle diagram right inside the PDF file:

prince: loading image: builds/pdf/assets/images/ch01/process.svg prince: used font: Menlo, Bold prince: used font: Menlo, Regular

Here’s what same diagram looks like in the final version of Ruby Under a Microscope:

The reason this looks better is that the end user PDF viewer app, Apple Preview, Adobe Reader, iBooks or whatever software your reader has, draws the diagram text at the proper size at the moment the reader opens the page, using the font that PrinceXML embedded into the PDF file.

EPUB tip: package many small HTML files, not one large one

While writing Ruby Under a Microscope I also became familiar with the EPUB file format. It’s a useful file format because it’s become an open standard shared by a large number of eBook reader devices. You can read EPUBs on a high end device like an iPad, on a variety of Android tablets, and also on cheaper eBook readers.

An EPUB file is really just a ZIP file that contains a HTML/CSS web site, along with a few confusing, bizarre XML files. In fact, in hindsight I’ve realized that an EPUB file closely resembles a J2EE web application - but without the Java! You might remember J2EE from the early 2000s and 1990s - it was how we created web sites before Rails came along in 2004 and made all our lives easier.

Unzipping my EPUB file, here’s what you’ll see:

$ unzip ruby-under-a-microscope.epub Archive: ruby-under-a-microscope.epub extracting: mimetype inflating: META-INF/container.xml inflating: OEBPS/assets/css/page-template.xpgt inflating: OEBPS/assets/css/stylesheet.epub.css inflating: OEBPS/assets/images/canvas-ana.png inflating: OEBPS/assets/images/ch01/ast-compile1.png inflating: OEBPS/assets/images/ch01/ast-compile2.png inflating: OEBPS/assets/images/ch01/ast-compile3.png inflating: OEBPS/assets/images/ch01/ast1.png … etc … inflating: OEBPS/ch04-part6.html inflating: OEBPS/ch05-part1.html inflating: OEBPS/ch05-part2.html inflating: OEBPS/ch05-part3.html inflating: OEBPS/ch05-part4.html inflating: OEBPS/ch05-part5.html inflating: OEBPS/ch05-part6.html inflating: OEBPS/conclusion.html inflating: OEBPS/content.opf inflating: OEBPS/cover.html inflating: OEBPS/preface.html inflating: OEBPS/title.html inflating: OEBPS/toc.html inflating: OEBPS/toc.ncx

It really does look like a committee of Java programmers designed the EPUB spec! We have something called “META-INF/container.xml,” a directory called “OEBPS,” and there are lots of confusing XML files with names like content.opf and toc.ncx. These all need to contain the proper information in precisely the correct format. Fortunately, as I mentioned above, the Bookshop gem runs the EpubCheck tool to validate that all the information in these files is correct.

On of the drawbacks of the Bookshop gem was that I had to write some Ruby code myself to generate the table of contents information stored in the “toc.ncx” file, and also the list of HTML and image files contained in the “content.opf” file. In hindsight the Kitabu gem might have taken care of this detail for me. Ideally the TOC info should be autogenerated from the <h1> or <h2> tags I use in my text.

One other important detail here: you’ll notice my HTML content is split up into a series of different HTML files: “ch04-part6,” “ch05-part1,” etc. Originally Bookshop created a single, large HTML file containing the entire text of the book and included that in the EPUB file. However, then I heard from Avdi Grimm and other readers than it was slow on some EPUB reader devices. The problem was that the reader device would hang while opening up the large HTML file, trying to render 100s of pages all at once.

With some help from Mike Cook I was able to fix this by splitting my text up into smaller HTML files. I did this by further customizing Bookshop, but I suspect Kitabu or other tools out there can do this automatically for you.

MOBI tip: use relative font sizes and Amazon CSS media types

Finally, to produce a book you can read on all of the different Kindle devices, the most popular eBook reader in the U.S., you need to create a MOBI file. Ironically, the MOBI format wasn’t even invented by Amazon, but now Amazon is the only reason this format continues to be relevant. As I explained above, Bookshop does this by running the KindleGen utility, from Amazon. I’ve heard rumors Amazon might directly support EPUB in the future, which would make all of our lives easier.

Be sure to download and use the Kindle Previewer app. This allows you to see how your MOBI file will render on seven or more different varieties of the Kindle. eBooks appear somewhat differently on each version of the Kindle and without this app there’s no way to know what will happen.

Using the Kindle Previewer with Ruby Under a Microscope I ran into trouble rendering fonts on some versions of the Kindle. Newer versions of Kindle, like the Kindle Fire, worked well, while older Kindles had trouble when I used certain fonts. More trial and error revealed that I could use only relative font sizes in my CSS code: font-size: 50% instead of font-size: 10pt, for example. I was also able to distinguish between newer and older Kindles using this special CSS media type directive invented by Amazon:

@media amzn-mobi

{

.section-caption {

text-align: left;

font-style: italic;

font-size: 50%;

}

}

@media amzn-kf8

{

.section-caption {

text-align: center;

font-style: italic;

font-size: 75%;

}

}

Why go to all this trouble?

If you made it this far, then you must really be interested in self-publishing. I have to admit that the technical work involved with producing an eBook myself was far more tedious and difficult than I had ever thought it would be. I can imagine that partnering with a publishing company would make this all a lot easier - probably you would be able to work within an established, proven technical publishing pipeline. But one of the joys of self-publishing is being able to have full control over the final product. There’s something thrilling and fun about controlling every last detail yourself. I hope this post saves you a few hours of frustration when it comes time to produce your eBook, or that it provides you a bit of encouragement to take the first step!