Why You Should Be Excited About Garbage Collection in Ruby 2.0

|

| While not very glamorous, Bitmap Marking Garbage Collection is a dramatic, creative innovation! |

You may have heard last week how Innokenty Mihailov’s great Enumerable::Lazy feature was accepted into the Ruby 2.0 code base. But you may not have heard about an even more significant change that was merged into Ruby 2.0 in January: a new algorithm for garbage collection called “Bitmap Marking.” The developer behind this sophisticated and innovative change, Narihiro Nakamura, has been working on this since 2008 at least and also implemented the “Lazy Sweep” garbage collection algorithm already included in Ruby 1.9.3. The new Bitmap Marking GC algorithm promises to dramatically reduce overall memory consumption by all Ruby processes running on a web server!

But what does “bitmap marking” really mean? And exactly why will it reduce memory consumption? If you know Japanese you can read a detailed academic paper published in 2008 by Narihiro Nakamura along with Yukihiro (“Matz”) Matsumoto. I was so interested I spent some time this week studying the garbage collection code in MRI Ruby myself, and this article will summarize what I learned. You won’t get any Ruby programming tips here today, but hopefully you’ll come away with a better understanding of how garbage collection actually works internally, of why Ruby 2.0 is something to look forward to, and of how innovative and creative the Ruby core developers really are.

Mark and Sweep

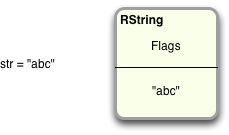

As I explained in my article from January, Never create Ruby strings longer than 23 characters, every Ruby string value is saved internally by MRI in a C structure called RString, short for “Ruby String.” Each RString structure is split into two halves like this:

At the bottom we have the actual string data itself, while at the top I’ve shown the word “flags” to represent various internal metadata values about the string that Ruby keeps track of. It turns out that all values used by your Ruby program are saved in similar structures called RArray, RHash, RFile, etc. They all share the same basic layout: some data and the same set of flags. The common name for this type of structure, which is shared across all the internal object types, is RValue - meaning “Ruby Value.”

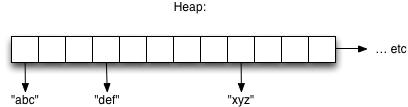

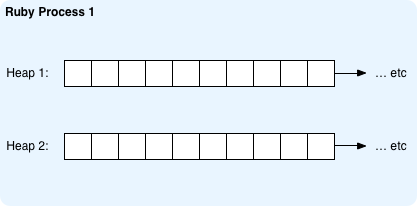

Ruby allocates and organizes these RValue structures in arrays called “heaps.” Here’s a conceptual diagram of a Ruby heap array, containing the three string values along with many other RValue’s:

As your Ruby program runs, whenever you create a new variable or value of some type the Ruby interpreter finds an available RValue structure in the heap and uses it to save the new value. Of course, you don’t need to worry about this at all; it’s all handled automatically and smoothly for you.

Well - it’s not that smooth at times, actually. What happens when the RValue structures in the heap run out? ...when there are none left to save a new value your program requires? This actually happens more frequently than you might expect because there are many RValue structures that you might not be aware of created internally by Ruby. In fact, your Ruby code itself is converted into a large number of RValue structures as it is parsed and converted into byte code.

When there are no more RValue structures available and your program needs to save a new value, Ruby runs its “garbage collection” (GC) code. The garbage collector’s job is to find which of these RValue’s are no longer being referenced by your program and can be recycled and reused for some other value. Here’s how it works, at a high level....

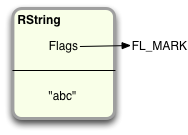

First, the GC code “marks” all of the active RValue structures, That is, it loops through all of the variables and other active references that your program has to RValue structures, and marks each one using one of those internal flags called FL_MARK.

This is the first half of Ruby's “Mark and Sweep” GC algorithm. The marked structures are actively being used by your Ruby program and cannot be freed or reused.

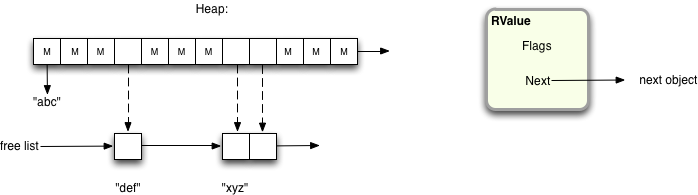

Once all the structures in the system are marked, the remaining structures are “swept” into a single linked list using the “next” pointer in each RValue structure: In this diagram, I’ve shown the FL_MARK flags in the heap array with the letter “M,” and below that you can see the list of unmarked RValue’s, called the “free list:”

As you might guess, the free list can now be used to provide new RValue structures to your Ruby program as it continues to run. Now every time your Ruby program allocates a new object or value, it uses an RValue from the free list, and removes it from the list. Eventually the free list will become empty again and Ruby will have to start another garbage collection.

After a while it might be that there are no unmarked structures left in the heap at all, that all of the available RValue’s are being used, in which case Ruby will allocate an entire new heap with more RValue structures. (Actually it allocates new heaps 10 at a time.) A typical Ruby program might end up having many different heap arrays.

Copy-On-Write: how Unix shares memory across different child processes

Before we can get to “Bitmap Marking” and why it’s important, we first need to learn about a feature of Linux and other Unix and Unix-like operating systems that is related to memory management and memory allocation: Copy-On-Write optimization. On these OS’s when a process calls fork to create a child process which is a copy of itself, the new child process will share all of the memory - all of the data, variables, etc. - that the parent had previously allocated. This makes the fork call much faster by avoiding copying memory around unnecessarily, and also reduces the total amount of memory required.

This is called “Copy-On-Write” because separate copies of a shared memory segment are made when and if one of the child processes tries to modify the shared memory. This is similar to the trick that the Ruby interpreter itself uses to manage RString values; for details check out a post I wrote in January about this: Seeing double: how Ruby shares string values.

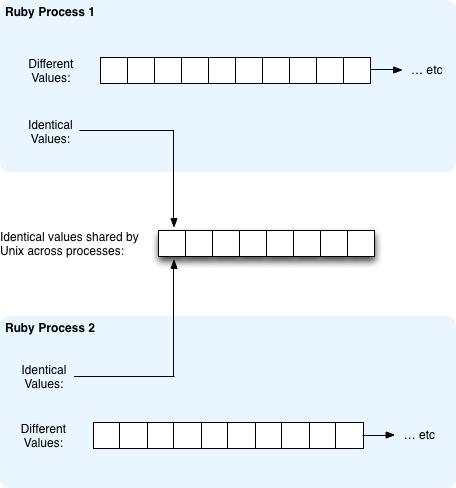

To understand this better, take a look at this conceptual diagram of a Ruby process:

Here I’ve shown a Ruby program that has two heaps as an example. Now suppose this Ruby program is running on a web server - maybe it’s a Rails web application - and now a second HTTP request arrives from another user:

Now we have two Ruby processes running. Possibly this server is running Apache with something like Passenger that forks a separate Ruby process to handle each HTTP request.

The nice thing about Copy-On-Write optimization in Linux is that many of the RValue structures in the heap arrays can be shared between these two Ruby programs, since they often contain the same values. It might not seem that this would be the case at first glance; why would many - or any - of the variables in two Ruby programs be the same? But remember on a web server you are actually running two or more copies of the same code, creating the same variables over and over again. Also, many of the RValue structures in the heap actually correspond to the parsed version of your Ruby program itself - the nodes in the “Abstract Syntax Tree” (AST). Since each process is running the same code, all of these nodes will have the same values and won’t ever change. Of course, some of the data values will be different and will be saved separately inside each process - user data typed into web forms and submitted, results of SQL queries on different records, etc.

But, as great as this sounds, it doesn’t actually work for Ruby!

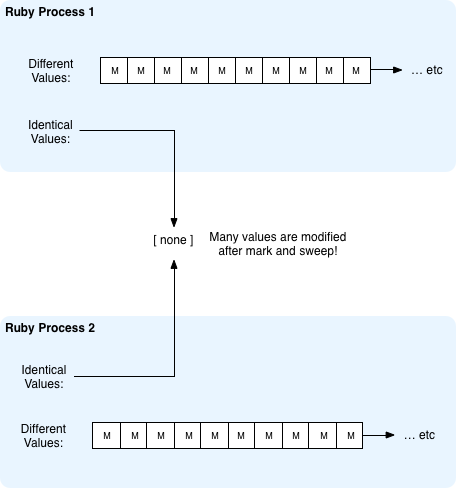

Why not? Well, because as soon as Ruby has to run the Mark & Sweep garbage collection algorithm I explained above, all of those AST nodes and many other RValue structures in the heap are all marked, since they are still being used by the Ruby program. This means they are modified to set the FL_MARK flag, and the Copy–On-Write code in the operating system has to start creating new copies of the memory. So in fact on a typical Ruby web server this is what happens:

That one little FL_MARK bit is wreaking havoc! It prevents what would normally be a tremendous reduction in server memory usage from actually happening.

One important note here: Hongli Lai from Phusion, the creators of the popular Passenger middleware component that connects Apache with Rack based Ruby apps, patched Ruby 1.8 and created a new version of Ruby known as Ruby Enterprise Edition that solves this problem and contains a number of other performance improvements. So in fact many Ruby 1.8 apps that use REE have been able to take advantage of Unix Copy-On-Write for years now. But Copy-On-Write still doesn’t work with standard MRI Ruby 1.8 or 1.9.

Garbage Collection in Ruby 2.0: Bitmap Marking

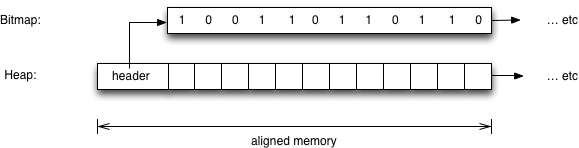

Here’s where Narihiro Nakamura’s changes for Ruby 2.0 come in! Instead of using the FL_MARK bit in each of the RValue structures to indicate that Ruby is still using an value and that it cannot be freed, Ruby 2.0 saves this information in something called a “bitmap” instead. No... here “bitmap” does not refer to an image file; “bitmap” in this context refers to a literal collection of bits mapped back to the RValue structures:

For each heap in Ruby 2.0 there is now a corresponding memory structure that contains a series of 1 or 0 bit values. As you might guess, the 1 values are equivalent to the FL_MARK flag being set in a Ruby 1.8 or Ruby 1.9 process, while a 0 is equivalent to the FL_MARK flag not being set. In other words, the FL_MARK bits have been moved out of the RString and other object value structures, and into this separate memory area called the bitmap.

Narihiro implemented this by adding a header structure to the beginning of each heap which contains a pointer to the bitmap corresponding to that heap’s RValue structures, along with some other values. What this means is that Ruby 2.0 can now mark all of the in-use structures during the “mark” portion of the GC processing without actually modifying the structures themselves, allowing Unix to continue to share memory across different Ruby processes! The bitmaps themselves, of course, are modified frequently by Ruby 2.0, but since they use a contiguous stream of bits they are actually quite small and can be saved separately in each process without using too much memory.

One interesting and important detail here is that the memory allocated for heaps now must be “aligned.” What this means is that when allocating memory for the heap, instead of calling malloc as usual, the Ruby C code calls posix_memalign which on a Linux or Unix operating system returns the new memory aligned to a power of two address boundary.

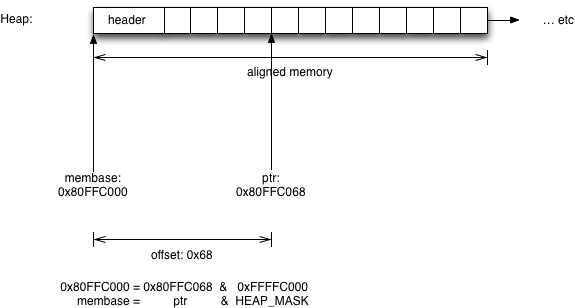

What the heck does that mean? Well if you’re familiar with C programming or bitwise arithmetic, it allows the Ruby C code to quickly calculate the location of the “header” structure, which contains the pointer to the bitmap, from a given RValue object’s memory address. Let’s take another look at a Ruby 2.0 heap:

Suppose that the Ruby 2.0 garbage collector code needs to mark the fifth RValue object in this heap, referred to by the ptr value. The memory alignment trick allows Ruby 2.0 to take the ptr value and quickly calculate the address of it’s heap header structure. All Ruby 2.0 has to do is mask out the last few bits of the RValue address, the “68” hexadecimal offset in this example, to obtain the address of the header structure, at “membase” or 0x80FFC000 in this 32-bit example.

Conclusion

Garbage collection isn’t the most glamorous or interesting part of the Ruby language at first glance, but as we’ve seen if you take a close look at how it works there’s a lot of interesting innovation going on. Practically speaking, the Bitmap Marking change will help MRI Ruby 2.0 work better in production web server environments, reducing memory consumption dramatically. But I view Bitmap Marking less as a practical improvement that will help my Rails apps run better, and more just as an exciting, creative solution to a complex problem. It was great fun learning how GC works in Ruby 2.0 and I hope you now have a better appreciation of all the hard work the talented Ruby core team is doing!