Learning From the Masters: Sinatra Internals

|

| More than a web framework, Sinatra is an elegant, stylish Ruby program we can all learn from |

We all know Sinatra as a lightweight alternative to Rails. I find using it is a real pleasure. Sinatra’s helper methods, template support and routing provide just enough to get a simple web site running quickly, but then immediately get out of your way. Years after it was introduced Sinatra remains one of the most popular Ruby web frameworks out there.

This week I decided to take a look inside of Sinatra to see what I could learn from the way it was written. I expected to find sophisticated, well written code that effectively implemented Sinatra’s API. What I didn’t expect to see was code written with a real sense of style and polish... Sinatra’s internals live up to the name!

Today I’ll show you three examples of this: how Sinatra calls your code via throw and catch, how Sinatra uses Test::Unit in a very readable and DRY manner, and how it uses metaprogramming in an elegant way that makes it easier for client code to use. Read on to learn more...

Using throw/catch to control program flow

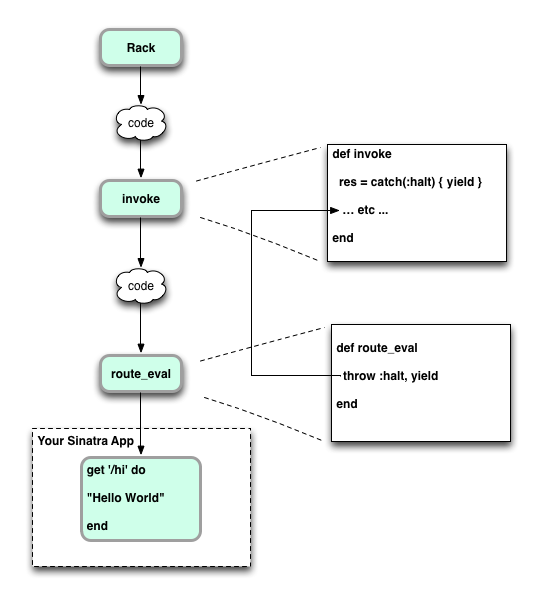

If you’ve ever used or read about Sinatra, you’ll remember that you provide code to handle HTTP requests using a series of blocks and route patterns. Here’s the basic example from the Sinatra web site:

get '/hi' do "Hello World!" end

Looking at Sinatra’s internals, the first thing I wanted to find out was how it called these code blocks. I expected to see some sort of loop, checking whether the current HTTP request path matched each route’s pattern, and indeed you can find this loop in the Sinatra::Base.route! method. But what I didn’t expect to see was how Sinatra implemented the actual call to the client’s route code block. This happens in a method called route_eval in Sinatra::Base:

|

# Run a route block and throw :halt with the result. def route_eval throw :halt, yield end

Huh? What’s going on here? The yield statement makes sense: since the client provides the route code as a block, Sinatra needs to yield to it. But what is the throw statement doing? And what does :halt mean? Is my route block somehow returning an error or exception? And where is it thrown to?

Before understanding what throw is doing here, we need to review how throw and catch work in Ruby, and how they are different from raise and rescue. I won’t spend time here today explaining that since Avdi Grimm wrote a fantastic article about exactly this question last Summer: Throw, Catch, Raise, Rescue… I’m so confused! He even used Sinatra as one of his examples. In a nutshell, Avdi explained that despite the different names, raise/rescue should be used to handle exceptions, similar to try/throw/catch in C++, Java and other languages. In Ruby, on the other hand, throw and catch are intended to be used as another program control structure.

Let’s take a look at how Sinatra uses throw and catch:

Here you can see that after one of your route code blocks returns a value to route_eval, Sinatra jumps back up the call stack to a method called invoke, where it had actually started processing the current request earlier:

# Run the block with 'throw :halt' support and apply result to the response. def invoke res = catch(:halt) { yield } ... etc ... end

Ruby sets the catch block’s return value to the second argument passed to throw - your route code block’s return value in this case, or res in the diagram.

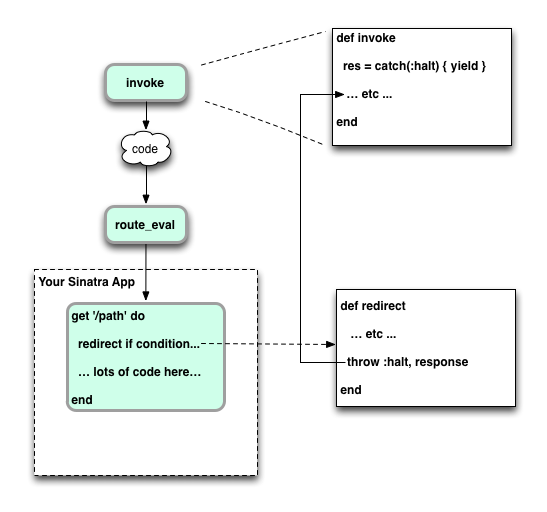

This is just the simplest example of throw in Sinatra - it turns out that many of the helper methods like last_modified, redirect, error, etc., all use throw to jump back to the invoke in a similar way, providing the appropriate return value. Here’s another example showing how Sinatra’s redirect helper method works:

The big benefit here is that when the client code decides to call redirect, Sinatra avoids the need to execute everything following the redirect call (“... lots of code here...”) - or the need for the client code itself to have to use an if/else statement to avoid executing it. Sinatra has taken what should be a normal, mundane Ruby programming task - calling a code block - and done it in a stylish, elegant way. The result is faster, cleaner code, both for Sinatra’s internals and for you!

A readable and maintainable test suite

Something else in Sinatra’s internals that caught my eye was the way it used Test::Unit. Many Ruby developers today prefer to use RSpec or Minitest instead of Test::Unit to get a more powerful and readable DSL for unit tests and BDD. But Sinatra, like the Rails core team, uses plain old Test::Unit for its test suite.

But what a minute... let’s take a look at some of Sinatra’s tests:

class BaseTest < Test::Unit::TestCase ... etc ... describe 'Sinatra::Base subclasses' do class TestApp < Sinatra::Base get '/' do 'Hello World' end end it 'include Rack::Utils' do assert TestApp.included_modules.include?(Rack::Utils) end it 'processes requests with #call' do assert TestApp.respond_to?(:call) request = Rack::MockRequest.new(TestApp) response = request.get('/') assert response.ok? assert_equal 'Hello World', response.body end

This doesn’t look like Test::Unit at all! Instead, it seems like Sinatra is using RSpec - why do I see the describe and it keywords here? Well it turns out that Sinatra has employed a neat little library called contest, which is adds support for describe/context blocks in Test::Unit, like you would see with RSpec or Shoulda. Sinatra has also defined the it keyword as an alias for test like this:

|

class Test::Unit::TestCase include Rack::Test::Methods class << self alias_method :it, :test ... etc ...

These two changes to Test::Unit have made Sinatra’s test suite much more readable... more stylish! But there’s also substance to the style: for example, notice the nice way that Sinatra created an entire test app right inside a describe block:

describe 'Sinatra::Base subclasses' do class TestApp < Sinatra::Base get '/' do 'Hello World' end end

Now subsequent tests can refer to this test application and see if Sinatra is handling things correctly; for example:

it 'processes requests with #call' do assert TestApp.respond_to?(:call) request = Rack::MockRequest.new(TestApp) response = request.get('/') assert response.ok? assert_equal 'Hello World', response.body end

Wow - that’s so simple and easy to read. Here Sinatra is also taking advantage of the excellent Rack::Test library by Bryan Helmkamp, which provides the Rack::MockRequest object.

I was also impressed with the way Sinatra’s test suite was very DRY - here’s are some more tests from the erb_test.rb file:

it 'renders inline ERB strings' do erb_app { erb '<%= 1 + 1 %>' } assert ok? assert_equal '2', body end it 'renders .erb files in views path' do erb_app { erb :hello } assert ok? assert_equal "Hello World\n", body end

These two tests and many other tests in the same file use the erb_app method to create a test Sinatra app and yield to the provided block in that app’s context. Sinatra achieves that by using a helper method at the top of erb_test.rb:

def erb_app(&block) mock_app { set :views, File.dirname(__FILE__) + '/views' get '/', &block } get '/' end

And Sinatra defines mock_app in the helper.rb file:

# Sets up a Sinatra::Base subclass defined with the block # given. Used in setup or individual spec methods to establish # the application. def mock_app(base=Sinatra::Base, &block) @app = Sinatra.new(base, &block) end

Sinatra has DRY-ed up its test suite substantially using these two helper methods, along with other, similar methods. Not only is Sinatra’s test suite easier to read for this reason, but it’s also easier to maintain. In my own personal projects I often don’t apply the same amount of love and attention to my test code as I do to my production code - there’s definitely a lesson to learn here!

Metaprogramming with style

One Sinatra feature you may not be familiar with is registering extensions to Sinatra’s standard DSL. Here’s the example they use in their documentation on Writing Extensions:

require 'sinatra/base' module Sinatra module LinkBlocker def block_links_from(host) before { halt 403, "Go Away!" if request.referer.match(host) } end end register LinkBlocker end

Once you’ve registered an extension module like this, you can use it from your Sinatra app like this:

require 'sinatra' require 'sinatra/linkblocker' block_links_from 'digg.com' get '/' do "Hello World" end

What interested me about this was the way Sinatra implemented the register method internally. Let’s take a look at that:

# Register an extension. Alternatively take a block from which an # extension will be created and registered on the fly. def register(*extensions, &block) extensions << Module.new(&block) if block_given? @extensions += extensions extensions.each do |extension| extend extension extension.registered(self) if extension.respond_to?(:registered) end end

While this might be a bit hard to understand at first, it’s actually fairly straightforward. The client code (your Sinatra app) passes in an extension, like the call to register LinkBlocker we saw above. Next this extension module is added to an array called @extensions and then Sinatra iterates over the array and extends itself with each extension.

This sounds fairly mundane and simple - I would have used much simpler code than this to do that same thing! What else is going on here?

|

Like a lot of the code inside Sinatra, the register method was not just implemented in a straightforward way - it was done with a real sense of style! Let’s take a closer look at some of the details here:

- First, the use of *extensions instead of just extension. This allows the client code to pass in a single extension, or a list of extensions as desired. This is a very common Ruby idiom, and Sinatra makes good use of it here.

- Next, notice the line of code containing the call to Module.new. This is more subtle and interesting. Here Sinatra is allowing the client code to pass in a block instead of, or in addition to, actual modules. If a block is given by the client code (block_given?) then Sinatra creates a new, anonymous module right on the spot with the block! Then it adds the anonymous module to the extensions array. This gives the client code the flexibility to pass in actual modules and/or anonymous blocks of code.

- Finally, notice the line near the end that calls respond_to?. What’s this all about? Well, here Sinatra checks whether the new extension module contains a method called registered. If it does, it calls that after applying the extension. This gives the client code the option of implementing the registered method if it needs to take some action at this point.

By paying attention to these minor metaprogramming details, Sinatra has added a lot of flexibility to the register method and made the client code’s job easier. You can find similar examples of this in other metaprogramming employed elsewhere in Sinatra’s code base.

Conclusion

All of these are all fairly minor details, but in my mind they raise Sinatra’s internal code from something normal and ordinary up to a higher level - to be something stylish and exceptional. The Sinatra developers weren’t satisfied with building just another web framework. They wanted to build something special that people would love to use. And the way they achieved this was by paying attention to the small design and code details that most Ruby developers - like me - would probably ignore.